History

Because the territories occupied by the De’áruwa were isolated and nearly impossible to penetrate, contact with the outside world was sporadic until the mid-twentieth century.

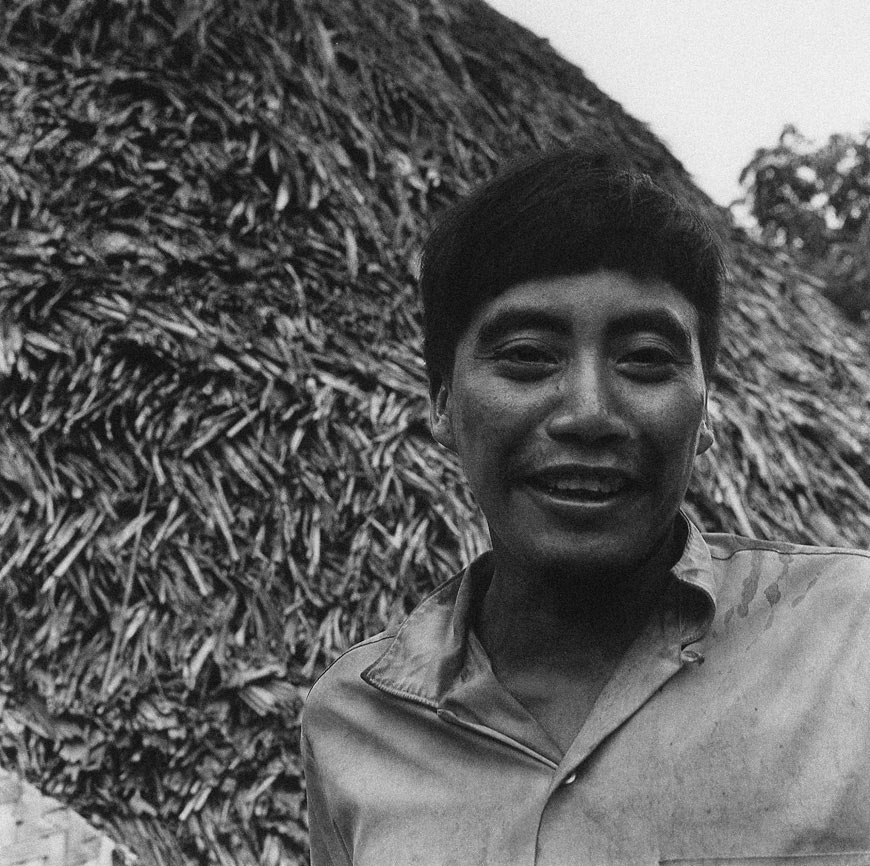

The De’áruwa speak a language in the Sáliva family, although some words are borrowed from Arawak and Caribe languages. They call all creatures that are born, live, and die in the jungle "De'áruwa", and refer to themselves as the “lords of the jungle.” In ethnological literature, they are also called Piaroa.

Environment

The De’áruwa have traditionally inhabited areas of tropical rain forest on the right bank of the Orinoco in which occasional bare sandstone formations rise through the canopy. Contact with missionaries and government officials in the 1950s caused epidemics. In the aftermath, many De’áruwa moved closer to criollo villages in order to be near medical treatment.

The De’áruwa inhabit areas surrounding the tributaries and sub-tributaries of the Puruname, Sipapo, Autana, Cuao, Guayapo, Samariapo, Cataniapo, Paria, Pargau, and Upper Suapure rivers. They also inhabit the lower basin of the Ventauri and the valley of Manapiare, the surroundings of Puerto Ayacucho and the Colombian margins of the Orinoco.

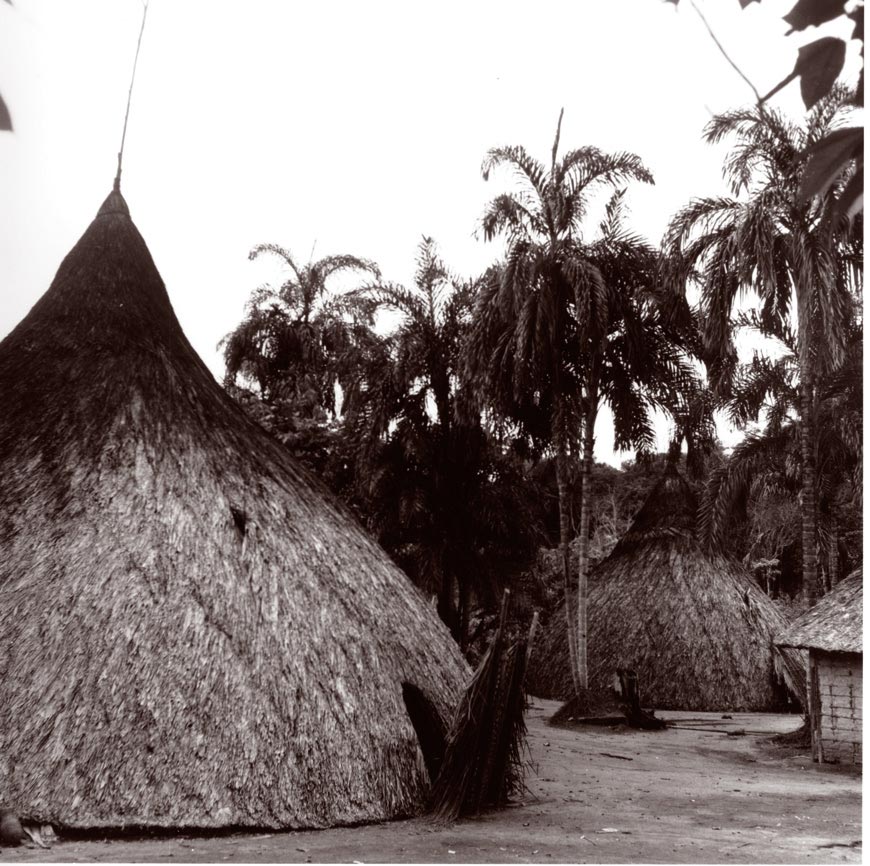

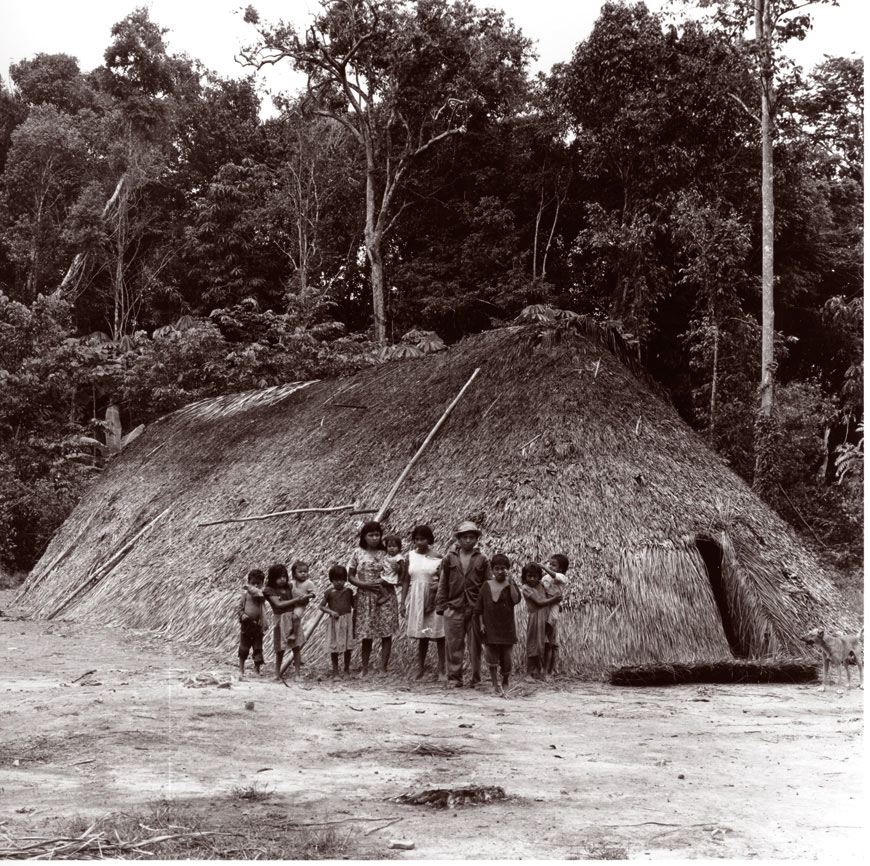

De’áruwa settlements consist of a group of communal family homes called churuatas. Although rudimentary in appearance, the churuata is a synthesis of symmetry and utility.

The De'áruwa build their traditional communal churuata with a short dome shape, with a conical roof made of palm leaves. It may measure as much as 18.5 yards across and 13 yards high, and house between 5 to 100 people. Inside the churuata, dimly lit by torches, is a network of beams and girders mounted in concentric rings.

Although there are no physical structures to divide families within a churuata, each family has its own area for storing belongings, sleeping in hammocks, and cooking. All of the churuata's inhabitants are free to use the central area, where they can gather to perform rituals, make crafts, and entertain guests.

Ritual and Tradition

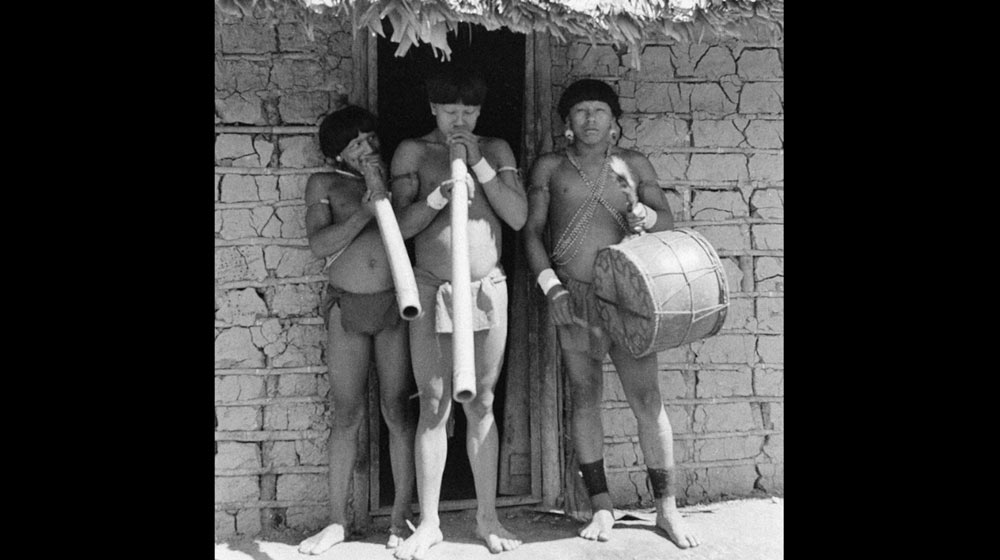

The De’áruwa adorn their bodies with dyes and decorations infused with symbolism. They create musical instruments on which they play magic ritual songs that relate myths of the animal world. The complex Warime ritual is a reenactment of the creation of the world involving music, dance, masks, and the passage of ritual knowledge.

Traditionally, De’áruwa men and women wear loincloths woven of cotton harvested from their own conucos. They adorn their bodies with feathers as well as crowns, bracelets, and necklaces. They create necklaces with alligator or báquiro teeth threaded together with multicolored feathers.

The more experienced of the De’áruwa men construct the masks used in the Warime ritual. No one person creates a particular mask; rather, it is a communal effort. The symbolic significance of each mask comes about in the process of construction.

The men use various materials to give the masks shape, and, in the final step of the process, the masks are painted and attains a status identical the animal spirit it represents.

De’áruwa musical instruments imitate the sounds of ancestral animals. The wora, for example, is a bamboo flute that when played mimics the sound of a jaguar's growl. Other flutes imitate the sound of the toucan or the screech of the howler monkey. Although considered sacred objects, today many of these instruments are also made for commercial sale.

The monkey mask for the Warime dance symbolizes the De'áruwa creational myth.

The most important De’áruwa ritual is the warime, a fertility ceremony practiced every three years. For this ceremony, the De’áruwa summon their mythical ancestors, the báquiros (peccaries). For the warime ceremony, the De'áruwa make sacred objects like masks, musical instruments, and special garments. The masks represent the báquiro; the white monkey; and Re’yo, the evil spirit of the bee.

Sustenance

As is common in the Amazonas region, the De’áruwa clear plots near their dwellings for farming; hunt; fish; and gather food from the forest. They have a sophisticated botanical knowledge that allows them to select and prepare plants for food, rituals, medicine and poison for hunting.

The De'áruwa, like the Ye'kuana people pictured here, grate bitter yucca as part of the process that makes it edible.

Everyday life involves farming in conucos during the rainy season. These conucos, or farm plots, are tended near the churuatas. De’áruwa grow plantains, sweet potatoes, sugar cane, pineapples, cotton, and, especially, bitter yucca, their main staple.

The De’áruwa also gather wild fruit, insects, and snakes from the forest for consumption. Small expeditions consisting of men, women, and children forage together. Upon their return, the goods they have gathered are shared with everyone in the communal home.

Fabrication

Men fabricate the objects needed for the Warime ritual in secret, in a structure off limits to the women, but other artisanal activities take place in the communal churuata's central area.

Some large De’áruwa settlements have a high level of cooperation that allows individuals to choose which activities to pursue. A De’áruwa man is not, for example, forced to go hunting if he would rather weave baskets. The craft of basketry for the De’áruwa is principally utilitarian. Among the baskets they weave are catumares, mapires, sebucanes, and guapas.

As is the case with other indigenous groups, pottery making has virtually disappeared since the introduction of aluminum and plastic containers. In the region of Alto Cuao, however, the De’áruwa do make pots and other clay containers that they use to store food and drink.